Multidisciplinary team meetings: what does the future hold

for the flies raised in Wittgenstein’s bottle?

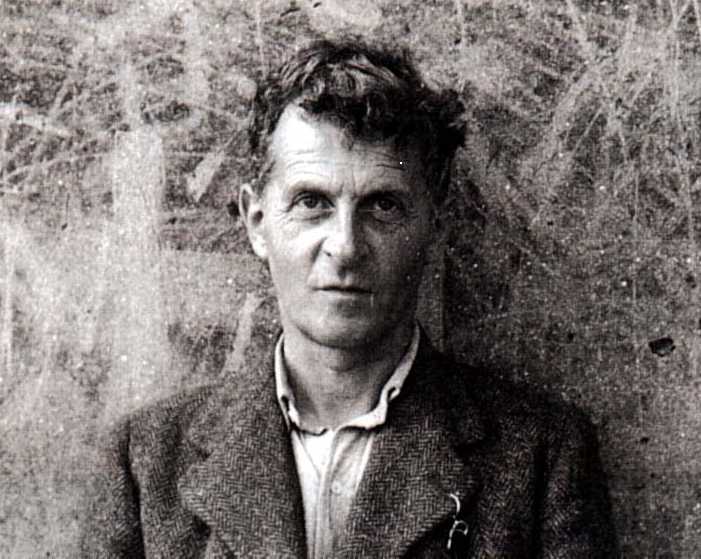

Ludwig Wittgenstein , filosofo : Vienna 1889-Cambrige 1951

fonte Lancet Oncology vol 10, febbraio 2009 pp 98-99

Do multidisciplinary cancer team meetings compromise

patients’ autonomy and the training of junior doctors?

Multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings bring together

health-care professionals with specialist knowledge

of diagnosis and treatment. In oncology, this should

include surgeons, diagnostic and therapeutic radio-

logists, histopathologists, medical and clinical onco-

logists, nurse specialists, dietitians, psychologists, and

palliative-care physicians. At least 80% of all cancer

cases in England are thought to be discussed at MDT

meetings.

1

It has also been argued that every specialist

attending an MDT meeting is legally responsible for

their area of expertise, because it pertains to the group

decision that is reached, even if the specialist does not

speak during the meeting.

2

There can be no doubt that the establishment of MDTs

has improved coordination and communication between

departments within hospitals and between hospitals

involved in joint meetings. The purpose of this article is

to discuss two “off -target” eff ects of the homogenous

adoption of MDTs as the routine standard of care in the

UK and to make a personal plea for two action points.

First, rather than discuss treatment options with an

individual patient in the clinic, it is not uncommon

for current oncology and surgical trainees to defer to

a higher body that is scheduled to meet at a later date.

Furthermore, trainees who have no active role in the

MDT are unlikely to develop independence of thought,

critical appraisal of treatment options available to

them, and the individuality of mind that comes with

making one’s own clinical decisions, observing the

results of one’s own clinical mistakes, and learning

from them. Publication of The Tractatus3

was an

important event in philosophy. In it, Wittgenstein

describes the principles of symbolism and the relations

between words and things that are necessary in

any language. Of note, Wittgenstein states “What

fi nds its refl ection in language, language cannot

represent”.

3

The deliberations of the MDT do not have

the same meaning for an individual who experiences

decision making with patients as compared with an

individual who does not. It should be remembered

that teaching involves conveying information whereas

learning requires engagement from the student

receiving the information. There is no substitute for

the active learning achieved when a trainee must

analyse the evidence base relevant to a patient and

speak confi dently and clearly with the patient and

with members of the MDT. Indeed, MDTs off er rich

opportunities for the education of trainees and medical

students, a feature that is currently forgotten in these

frenetic business meetings that often run beyond their

allocated timeslots.

The second issue we wish to address is the key

ethical principle of respect for patient autonomy.

It has been argued that, where all else is equal (eg, a

case where there is no robust evidence base from

clinical-trial data), autonomy should take precedence

over other ethical principles.

4

As autonomy has taken

centre stage, the structure and goals of the medical

consultation have come under scrutiny. An ideal

developed in general practice, but widely applied and

taught in hospital medicine, describes the consultation

as a “meeting of equals”, between the patient, as an

expert in their own experiences and goals, and the

Democratic Forum model

Patient told diagnosis and

stage of illness. Treatment

options will be discussed at

next clinic appointment.

Patient told diagnosis and

stage of illness. Treatment

options discussed and patient’s

views of various treatment

options documented.

MDT advocates single best

treatment option based on

majority view.

MDT presentation with

clear expression of patient’s

views about treatment options.

Range of possible options

discussed with MDT, with

documentation of provisos

regarding potential detriment

of certain options and named

specialists’ formal dissension.

If declined, patient’s case

might require discussion at

MDT meeting again.

Patient can accept or decline

offer of single best treatment

option. If accepted, treatment

is implemented.

MDT opinions presented to

patient. Decision making

done in clinic with patient.

This model presumes that decision making is con cen-

trated in the consultation.

Multidisciplinary teams have set local clinical stand-

ards, and we believe that important aspects of decision

making have ceded from the doctor–patient consultation

to the MDT meeting. In many cases, the consultation

with the patient might be used only to discuss the

outcome of deliberations by a specialist professional

and to gain the patient’s consent to proceed with the

best treatment option determined by committee. In

extreme cases, the doctor’s role is to present the MDT’s

majority decision rather than the consultant’s personal

opinion of various treatment options based on their own

knowledge and experience. Does this alter the patient’s

view of the professional in front of them?

We suggest the following actions to protect patient

autonomy and to educate trainee doctors. Recognising

that attendence of all patients at MDT meetings is

not a practical solution, individual teams should take

steps to include the patient’s perspective in the initial

presentation of the clinical case and in the decisions

that are reached. In a small number of MDTs in the UK,

such an approach is already considered best practice.

Teams can encourage the presence of individuals,

such as specialist nurses or a informed doctor, who have

consulted the patient explicitly, to act as their advocates

in the MDT meeting. The chairperson of the meeting,

who might be a specialist nurse or another individual

who is not biased towards a particular treatment,

should ensure that the loudest voice in the room does

not prevail in every case. Indeed, rather than a single

treatment recommendation based on the majority

view (fi gure), the team should be willing to advocate

a range of options that could be tailored to a patient’s

preferences in the subsequent consultation, albeit with

discussion of the potential detriment of not consenting

to the “gold standard” defi ned by the MDT. Moreover,

the doctor’s perspective might have to change. The

doctor with legal responsibility for the patient’s

treatment might consider the MDT as an interactive,

individualised source of approval. The MDT’s input

could be critically applied to each situation after the

consultation with the patient in which various options

are discussed and before the consultation in which

decision making takes place.

Most importantly for trainees, there should be time

allocated at the end of the MDT meeting for debriefi ng,

discussion of educational points, and for the opinions of

medical students and trainees to be heard. Trainees and

students should be set tasks to complete before the next

MDT meeting, that involve analysis of the evidence,

communication with the patient, and presentation

of fi ndings. Team working could be encouraged by

allocating tasks to small groups. Health professionals’

time is limited and costly, so the educational sessions

could be undertaken by a designated individual after the

other MDT professionals have left the meeting. This goal

can only be achieved if resources are allocated to protect

the time of the individuals involved.

Individuality of mind requires performance of the

deed and the ability for lateral thinking. Wittgenstein

described a fl y in a bottle, which buzzes against the glass

and cannot escape. Yet there is no stopper in the bottle;

the fl y needs to add a new direction to its fl ight. Perhaps

now is the time for us to add an educational dimension

to MDTs and let our fl ies fi nd their own way out of the

bottle.

Ricky A Sharma*, Ketan Shah, Eli Glatstein

Gray Institute for Radiation Oncology and Biology, University of

Oxford, Oxford, UK (RAS); Oncology Department, Churchill

Hospital, Oxford Radcliff e Hospitals NHS Trust, Oxford, UK

(RAS, KS); Department of Radiation Oncology, University of

Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA (EG)

ricky.sharma@rob.ox.ac.uk

Bibiography.

1 Fleissig A, Jenkins V, Catt S, Fallowfi eld L. Multidisciplinary teams in cancer

care: are they eff ective in the UK? Lancet Oncol 2006; 7: 935–43.

2 Sidhom MA, Poulsen MG. Multidisciplinary care in oncology: medicolegal

implications of group decisions. Lancet Oncol 2006; 7: 951–54.

3 Pears DF, McGuinness BF. Tractatus logico-philosophicus (translation).

London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1961.

4 Gillon R. Four scenarios. J Med Ethics 2003; 29: 267–68.

5 Tuckett D, Boulton M, Olson C, Williams A. Meetings between experts:

an approach to sharing ideas in medical consultations. London: Tavistock

Publications, 1985.

6 Blazeby JM, Wilson L, Metcalfe C, Nicklin J, English R, Donovan JL. Analysis

of clinical decision-making in multi-disciplinary cancer teams Ann Onc 2006, 17: 457-60

:::::: Creato il : 03/10/2009 da Magarotto Roberto :::::: modificato il : 03/10/2009 da Magarotto Roberto ::::::